Frequently Asked Questions

Why is an Office for Orphan Policy, Diplomacy and Development needed?

According

to UNICEF, 132 million children in the developing world are orphans,

meaning they have lost one or both of their parents. If the current

pace continues, 15 million more children will be orphaned this year

alone. At the same time, by the end of 2003, only 17 countries with

generalized epidemics reported having a national policy for orphans

and vulnerable children to guide strategic decision-making and resource

allocation. In 2007, The U.S. government reported spending $225

million, less that .7 percent of the U.S. foreign aid budget, on

Orphans and Vulnerable Children. What’s worse, very little of the

funding set aside to address the overall needs of orphaned children

is dedicated to activities designed to reconnect these children

with a responsible, loving parent. Similarly, global efforts, such

as the Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly in

2002, fail to recognize that connecting orphaned children with permanent

families is an important component of any universal child welfare

strategy.

According

to UNICEF, 132 million children in the developing world are orphans,

meaning they have lost one or both of their parents. If the current

pace continues, 15 million more children will be orphaned this year

alone. At the same time, by the end of 2003, only 17 countries with

generalized epidemics reported having a national policy for orphans

and vulnerable children to guide strategic decision-making and resource

allocation. In 2007, The U.S. government reported spending $225

million, less that .7 percent of the U.S. foreign aid budget, on

Orphans and Vulnerable Children. What’s worse, very little of the

funding set aside to address the overall needs of orphaned children

is dedicated to activities designed to reconnect these children

with a responsible, loving parent. Similarly, global efforts, such

as the Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly in

2002, fail to recognize that connecting orphaned children with permanent

families is an important component of any universal child welfare

strategy.

Part of the reason for this disconnect is that the U.S. is still reliant upon processes and programs that were established when the term “orphan” was used to refer to the thousands of children whose parents were killed as a result of World War II and the Korean War. In addition, responsibility for addressing the needs of these children has been divided up among various offices and bureaus within the federal government, each with its own focus and agenda.

For this to change, the U.S. needs to develop a comprehensive, forward thinking strategy for addressing the needs of orphaned children worldwide. To be successful, such a strategy must include activities aimed at preserving and reunifying families and providing permanent parental care for orphaned children. History shows that diplomatic leadership of this kind requires a focused and appropriately resourced effort led by the United States Department of State.

Isn’t this just creating more bureaucracy?

No. In fact, The Families for Orphans Act tries to reduce the bureaucracy that has stymied efforts on behalf of orphaned children by putting in place mechanisms to eliminate unnecessary duplication of efforts and better coordinate activities on behalf of orphaned children. The Office for Orphan Policy, Development and Diplomacy will not be a separate federal entity. Instead, it will be a focused office within the U.S. Department of State. In addition, its requirement that all federal entities with an interest in the area of orphans participate in a policy coordinating committee will eliminate the duplication of efforts and barriers to effective communication that too often lead to inefficiency in this area.

Faced with a similar dilemma in October 2001, the U.S. Congress had the foresight to create the Office to Combat Trafficking in Persons. To date, this office has radically transformed U.S. efforts to eliminate trafficking worldwide. The Families for Orphans Act emulates this and other models of effective diplomatic leadership by the United States.

Doesn’t the United States already spend millions on taking care of orphans?

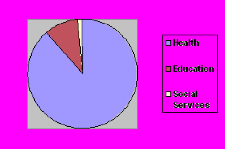

The following chart outlines the breakdown of U.S. efforts to “Invest in People” abroad.

As

the figure abroad demonstrates, the majority of foreign aid funds

are invested in health care, with 5.1 billion of the total 7.7 billion

going to AIDS. According to figures complied by Global Action for

Children, the U.S. spends approximately $225 million on addressing

the overall needs of orphans. This represents less than .7 percent

of total foreign aid. A review of the programs funded reveals that

the majority of the United States efforts are aimed at providing

housing, nutrition, health care, education and protection for orphans

and vulnerable children. What’s more, many of these programs are

restricted to those children who have been orphaned as a result

of AIDS. No doubt, these programs are necessary and the U.S. could

be spending more than they are currently in these areas. At the

same time, if the U.S. wants to address the long term needs of orphaned

children, then it must also encourage and fund programs aimed at

reconnecting orphaned children with a loving, responsible adult.

As

the figure abroad demonstrates, the majority of foreign aid funds

are invested in health care, with 5.1 billion of the total 7.7 billion

going to AIDS. According to figures complied by Global Action for

Children, the U.S. spends approximately $225 million on addressing

the overall needs of orphans. This represents less than .7 percent

of total foreign aid. A review of the programs funded reveals that

the majority of the United States efforts are aimed at providing

housing, nutrition, health care, education and protection for orphans

and vulnerable children. What’s more, many of these programs are

restricted to those children who have been orphaned as a result

of AIDS. No doubt, these programs are necessary and the U.S. could

be spending more than they are currently in these areas. At the

same time, if the U.S. wants to address the long term needs of orphaned

children, then it must also encourage and fund programs aimed at

reconnecting orphaned children with a loving, responsible adult.

How does this differ from the way things are now?

Under current law there are at least five different offices and bureaus engaged in work on behalf of orphans (Office of Children’s Issues (DOS); Orphans and Vulnerable Children Coordinator (USAID); PEPFAR, Office of the AIDS Coordinator; Population, Refugees and Migration). These offices are not working together to achieve the objectives of a unified comprehensive global strategy nor are they given the benefit of regular opportunities for coordination and communication. Under the current system, it is highly possible that the Office of Children’s Issues could be advocating for the deinstitutionalization of children at the same time that the Orphans and Vulnerable Children Coordinator is advocating for building an orphanage to house AIDS orphans.

At the same time, foreign governments are looking to the United States to provide leadership and dedicate resources to addressing this world crisis. Under current law, international and national meetings on the subject of orphans are attended by a wide variety of varying level officials, many of whom are attending such meetings by default. Foreign governments do not have the opportunity to engage in diplomatic conversations with a consistent, high level official.

Under the Families for Orphans Act, the United States would be represented by a U.S. Coordinator for Orphan Policy Development and Diplomacy. Aided by the information gathered by tools such as a biennial census and a global assessment, the Coordinator would be in a position to lead the U.S. to develop and implement a comprehensive strategy for addressing both the physical and emotional needs of orphans. Finally, through the work of an interagency Policy Coordinating Committee, the U.S. government would be better able to coordinate both domestic and international efforts on behalf of children in need of homes.

Would this bill impede the efforts of the United States to implement the Hague Convention on International Adoption?

No. It merely states that the new Office should represent the United States whenever there is a need for diplomatic representation on the issue of international adoption. One might argue that the Families for Orphans Act would actually expedite the full implementation of the Hague Convention in that it will provide the leadership and resources necessary to more appropriately address the need for international adoption systems that are both effective and ethical.

Does this bill conflict with Public Law PL 109-95?

No. The Families for Orphans Act does nothing to replace the structure put in place by PL 109-95. Under current law, the Special Advisor for Orphans and Vulnerable Children is engaged in efforts to ensure that the world’s children are receiving the health care, nutrition, education and the protection they need to survive. These activities would continue with the additional benefit of coordination and support from the Office of Orphan Policy Development and Diplomacy.

Just how many of the world’s children are in need of homes?

The simple answer is we don’t know. While UNICEF reports that there are 132 million orphaned children, a large percentage of these children have at least one living relative capable of providing them with a loving and safe home. It is for this reason that the Families for Orphans Act proposes that the U.S. engage in a biennial census so that we can better understand and respond to the needs of these children and their families.

In what ways does the US government support permanent parental care for children in developing countries such as Guatemala?

Sadly, the US government is not consistently engaged in helping developing countries find permanent parental care for children. In fact, in most countries the only permanency related intervention is through international adoption. What this means is that when international adoption slows down or is stopped all together, children are left without any viable opportunities to find permanent families. The Families for Orphans Act attempts to change this by putting in place a diplomatic structure for engaging in dialogue with world leaders and leaders of other countries regarding orphan policy and care. In addition, it provides the resources necessary to support the efforts of governments and non-governmental organizations to provide permanent parental care.

Help EACH continue to advocate on behalf of adopted children...more.

Help Support the Cause!

EACH needs your help to achieve equal treatment of all children of American citizens whether they were adopted by or born into an American family. Please voice your support for this cause by joining EACH. Membership is free!...More